This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

Read the magazine story to find out more. |

|

|

Scientists Probe "Fly Spit" for Clues to Serious Wheat Pest

By Erin PeabodyJanuary 8, 2007

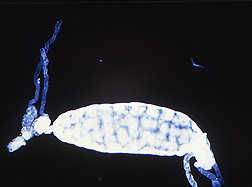

The Hessian fly, the No. 1 global pest of wheat, is not your ordinary insect. Its fiercest weapon—capable of making wheat plants droop, topple over and even commit cell suicide—is its deadly saliva.

Based on findings by scientists with the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Manhattan, Kan., the fly appears to put a lot of genetic stock in executing this unusual offensive. The ARS team has identified at least 2,000 genes that play some role in churning out the toxic salivary brew that the fly injects into wheat plants when taking a bite.

Led by entomologist Ming-Shun Chen, the researchers are zeroing in on these genes, in hopes of pinpointing those that make the destructive Hessian fly such an elusive pest.

For thousands of years, wheat plants and Hessian flies have been squaring off, with the fly trying to get access to its favorite food, as the wheat plants guard themselves from attack. For every one of wheat's resistance genes, there's a corresponding "avirulence" gene in the fly.

Even modern breeding efforts can't fully bolster wheat plants. At least four of the most recent resistance genes introduced into wheat plants no longer ensure an effective level of protection because of the fly's highly adaptive nature.

Chen and his team, who work at the Grain Marketing and Production Research Center (GMPRC) in Manhattan, have identified 97 "superfamilies" of genes in the fly that encode for toxic salivary proteins. This appears to be a hefty genetic investment, given the fly's minute genome, considered one of the smallest in the insect world.

The GMPRC researchers are also making progress in efforts to prop up fly-weary wheat plants. They've mapped several resistance genes in wheat, including the H9 and H13 gene clusters. These findings are helping breeders conduct marker-assisted selection, a method for "stacking" multiple protective genes into a single plant.

For more on ARS's Hessian fly studies, see the latest issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

ARS is the U.S. Department of Agriculture's chief scientific research agency.