This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

|

Read the magazine story to find out more. |

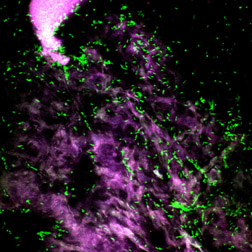

Food Poisoning Microbe Targeted in New StudiesBy Marcia WoodJuly 10, 2001 If a microbe can somehow cling to a food surface, it might be able to start a successful invasion. Now, Agricultural Research Service scientists are snooping into the secret tricks that food-poisoning organisms use when they grab onto chicken skin, for instance. Their studies may lead to new, safe, and effective ways to thwart pathogenic microorganisms such as Campylobacter. That microbe causes an estimated 2 million illnesses, 10,000 hospitalizations and 100 deaths a year in this country. Microbiologist Robert E. Mandrell and colleagues at the ARS Food Safety and Health Research Unit in Albany, Calif., are spying on Campylobacter jejuni, the most troublesome of the Campylobacter species. They want to determine how the microbe’s genes interact with molecules known as receptors. Preliminary experiments by Mandrell’s team at the ARS Western Regional Research Center in Albany are revealing details about two kinds of chicken-skin molecules that likely serve as receptors. The molecules are proteins called proteoglycans and fat-containing compounds called phospholipids. In a test with 12 Campylobacter strains, the researchers found that all of the strains bound to proteoglycans within about two minutes. In about 20 minutes, the Campylobacters formed large colonies. In another test, the scientists showed that eight of nine Campylobacter strains, when exposed to a mixture of chicken-skin phospholipids, bound to a phospholipid known as sphingomyelin. Other scientists have already speculated that proteins or fats in meats may act as receptors. The Albany investigations provide new evidence that proteoglycans and phospholipids probably play that role in poultry and show the speed with which the microbe can attach to receptors that it apparently prefers. Mandrell did the work with Anna H. Bates, David L. Brandon, Gary A. McDonald and William Miller, of the Albany team, and with Amy O. Charkowski, now at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. An article in the July issue of the agency’s Agricultural Research magazine tells more and can be viewed on the World Wide Web. ARS is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s chief scientific research agency. |