This page has been archived and is being provided for reference purposes only. The page is no longer being updated, and therefore, links on the page may be invalid.

Read the magazine story to find out more. |

|

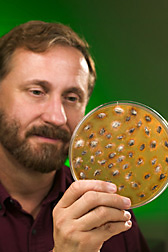

Seed-Rotting Microbes Sought to Battle Weeds

By Jan SuszkiwMay 10, 2006

New, integrated approaches to battling annual broadleaf weeds may enlist beneficial soil microbes that “hit” the pesky plants where it hurts—their seed banks.

These banks are reserves of thousands, even millions, of weed seeds that lie dormant beneath the soil awaiting favorable conditions to germinate, according to Joanne Chee-Sanford, a microbiologist with the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Urbana, Ill.

Since 2002, Chee-Sanford has been piecing together the conditions under which certain fungi and bacteria will cause decay in dormant weed seeds, killing them or diminishing their fitness. Classical biological control would call for unleashing the microbes onto a targeted weed to fight it, but Chee-Sanford has a slightly different tactic in mind. Rather than apply microbes as biological control agents, she envisions bolstering the activity of microbes that already occur in the soils naturally, possibly using an amendment of some kind.

The problem is, seedbank soils are home to many microbial species with different ecological roles to fill, notes Chee-Sanford, with the ARS Invasive Weed Management Research Unit. Some only eat carbon and other nutrients exuded in the soil by seeds, while others use means such as powerful enzymes to breach the seed, steal its nutrients and cause decay. Sometimes, seed decay is a multimicrobe effort.

In one study, for example, 99 percent of velvetleaf seeds underwent microbial decay after three months, particularly when the seeds were the only carbon available as food. The prime decay agents—Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria, found in many soils—are known to degrade natural seed polymers. But Chee-Sanford is still trying to ascertain whether they were the initial cause of the seeds' decay, or mere contributors.

Her efforts are part of a broader program within the Urbana unit to furnish midwestern farmers with new weed-management systems that integrate biological, chemical, cultural and mechanical control methods.

Read more about the research in the May 2006 issue of Agricultural Research magazine.

ARS is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s chief scientific research agency.